[Note: This article first appeared here.]

Welcome back for the second half of my article looking at trends in performance by US skiers (as a group) on the international scene. Â Last time we looked at distance events, so now it’s time to turn to sprinting. Â Before we move on, if you haven’t read the first half of this article, please go do so now. Â It can be found here. Â I laid out many important caveats in that piece that remain in effect here.

Our treatment of sprint racing will follow roughly the same strategy, with some obvious modifications. Â First, using FIS points as a metric for performance no longer makes much sense. Â They are only calculated on the qualification results, and while qualifying speed is certainly important, it doesn’t much matter if you can’t advance through the heats. Â Instead I’ll simply be using the final rank (or finishing place) after the heats. Â Simplistic, for sure, but it’s the best we’ve got.

The next big difference is time frame. Â Sprinting hasn’t been around as long as distance events. Â Worse, it’s early years were highly experimental, with FIS bouncing around on lengths and race formats. Â At various points in time anything from a 100m dash on skis to a 10k interval start (for men) has been considered a “sprint” race by FIS. Â So I’m going to try to restrict this analysis to races that are reasonably similar to the current sprint format, stretching back to the 2000-2001 season. Â If you push back much earlier, the number of sprint races drops off considerably and the formats just get more unpredictable. Â That leaves us with ten seasons of WC, OWG and WSC sprint races.

Before we move on to the graphs, I want to say a few words about the implications of looking at distance and sprint events separately. Â It is important to keep in mind that nobody had the opportunity to participate in sprint events prior to the late 90’s. Â I know that sounds obvious, but what it means is that we have no idea how good American, Canadian or Scandinavian skiers in the past may have been at sprinting. Â It’s possible that Bill Koch, Nancy Fiddler, Leslie Thompson or Ben Husaby all could have reached the podium in a sprint event had they been given the chance. Â Then again, maybe not. Â We’ll simply never know.

I point this out only because my statistician sensibilities make me particularly sensitive to inapt comparisons. Â So when we talk about how “good” or “bad” a sprinter (or team of sprinters) is, that statement only makes sense in the context of sprint racing in the past decade. Â Even that time frame is potentially debatable, since it has only been in the last 4-6 years that we’ve seen sprinters on the WC scene who’ve had the opportunity to participate in sprint races throughout their youth and junior development.

My intention here is not to downplay (or pump up) any perceived success or failure at sprint racing. Â The newness of sprinting doesn’t make Petter Northug’s or Emil Joensson’s talent at it any less impressive. Â Rather, I’m trying to caution you that comparing anyone’s success (or lack thereof) at sprinting to other athletes prior to the late 90’s just makes no sense.

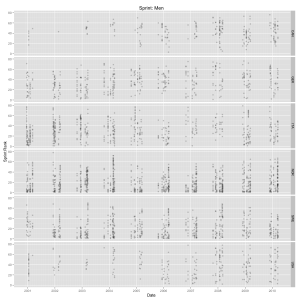

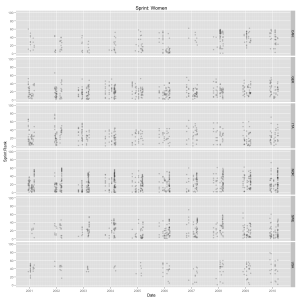

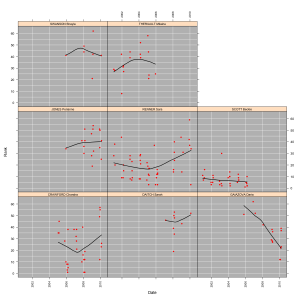

In any case, let’s begin with simple plots of sprint results for the past ten seasons for six different nations.

I’ve swapped Italy in for Russia, just for fun, but that’s the only change. Â As before, I find it difficult to make much sense of the data in this format. Â We’ll move on to the quantile trend line graphs that I introduced previously. Â They work exactly the same way, only now we’re using the raw finishing place, or rank, on the y axis rather than FIS points. Â Interpreting them is the same: it’s better to have lines close to the bottom, and for your trend lines to be bunched closer together.

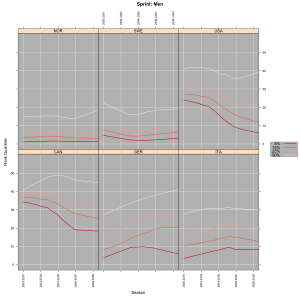

First the men: Norway, as before, has been somewhat boringly good. Â Sweden has been comparable, although perhaps tailing off just slightly. Â The German men certainly have some decent sprinters, but their team isn’t spectacularly deep, and their “second tier” racers seem to be sliding backwards somewhat. Â The Italians initially had some excellent sprinters, but again not nearly as deep a team as the Norwegians, and they also seem to have regressed slightly. Â The Canadian men enjoyed substantial post-Salt Lake Olympics improvement, but that improvement has slowed recently. Â Also, their gains in sprinting aren’t nearly as dramatic as their gains in distance racing.

The American men show steady improvement at sprinting, though not at all levels. Â Their median results have remained below the elimination round cutoff of 30th. Â After reading the first half of this article, you might guess where I’m headed: Andy Newell. Â He is clearly responsible for nearly all of this improvement. Â To what degree? Â On the left is a list of the number of sprint results in WC, OWG and WSC over the past ten season where the athlete made it past the qualification round:

| NEWELL Andrew | 48 |

| KOOS Torin | 29 |

| COOK Chris | 8 |

| KUZZY Garrott | 3 |

| WADSWORTH Justin | 3 |

| HAMILTON Simi | 2 |

| NASH Marcus | 2 |

| SWENSON Carl | 2 |

| CASEY Patrick | 1 |

| CHAMBERLAIN Dave | 1 |

| FREEMAN Kris | 1 |

| RODGERS Colin | 1 |

| WHITNEY Robert | 1 |

Basically half of these results are by Andy Newell and another third or so are by Torin Koos. Â Another 10% are by athletes that have retired.

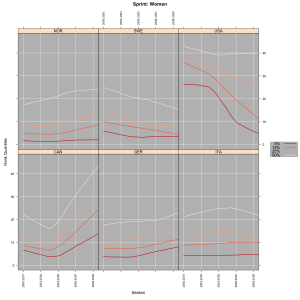

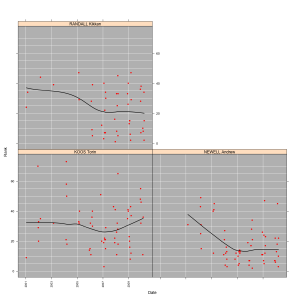

Let’s move on to the women. Â The Norwegian women have again been very good, though perhaps losing some depth recently. Â The Swedish women have been steadily improving, particularly by their “mid-range” WC skiers. Â The Italians have been fairly consistent and the German women seem to have been losing ground over the last few years.

The story for the Canadian women looks fairly dramatic, so we should look more closely here. Â Again, not surprisingly, the major story is Beckie Scott. Â The sudden uptick in their trend lines corresponds to two things: Beckie Scott’s retirement and Chandra Crawford’s inability to replicate her outstanding 2005-2006 season. Â So it’s not so much that the Canadian women have been getting slower, it’s that their major source for top results suddenly retired and they haven’t quite found a replacement. Â Looking at results broken down by individual summarizes all this nicely:

Note that the dramatic effect of Beckie Scott’s retirement initially obscured some positive news seen in the steady improvement by Daria Gaiazova.

The US women, like the US men, show evidence of significant improvement in sprinting, though mostly at the top end. Â Once again, the story here is Kikkan Randall. Â A list (on the right) of the number of times different American women reached the elimination round of a WC, OWG or WSC sprint race over the last decade is even more stark.

| RANDALL Kikkan | 29 |

| KEMPPEL Nina | 5 |

| WAGNER Wendy | 4 |

| BENOIT Tessa | 1 |

| BROOKS Holly | 1 |

| SMYTH Morgan | 1 |

| VALAAS Laura | 1 |

Nearly 70% of these results are by Kikkan Randall and another 20% or so are by athletes that have retired.

Finally, the final graph gives  a closer look at the sprint results of the USA’s top three sprinters (at least by past success and number of starts on the WC level).

I’m not going to repeat all the caveats and warnings that I listed in the first installment of this article; obviously they all still apply.

To recap, my aim was to put forth some data pertaining to the overall performance of the US (and Canada) in elite cross country ski racing. Â My intention was not to draw conclusions about the merits of any particular decisions or strategies by athletes or coaches. Â As I stated at the outset, I’m hardly qualified to do so. Â Instead, my goal has simply been to provide the beginnings of a common framework for future debate and discussions.

As I emphasized when I started this article, the key word in the previous statement is “beginning”. Â I do not claim these data represent some final or conclusive picture of the state of US skiing. Â However, I do hope that some may find it useful and interesting.

[ad#AdSenseBanner]

Post a Comment